Why Traditional Study Methods Are Failing Students (And What Actually Works)

Why Traditional Study Methods Are Failing Students (And What Actually Works)

It's 2 AM. You've been studying for six hours straight, highlighting passages and re-reading the same chapter for the third time. Tomorrow's exam feels overwhelming, and despite all your effort, you can't shake the feeling that most of what you've "learned" will vanish the moment you walk out of the testing room.

Sound familiar? You're not alone.

The Hidden Crisis in Student Learning

While 92% of students now use AI tools to enhance their studies, the fundamental approach to learning hasn't evolved. The statistics reveal a troubling reality:

- 65% of college students struggle to maintain consistent study habits

- 85% believe better time management would improve their academic performance

- 58% submit assignments within 24 hours of the deadline, despite having weeks to prepare

- Over 60% forget new material within a week without structured review

Perhaps most telling: students are working harder than ever, yet retention rates continue to decline. The problem isn't effort—it's method.

The Illusion of Learning: Why Highlighting and Re-reading Don't Work

Most students rely on what researchers call "passive learning strategies." You know them well:

- Highlighting important passages in textbooks

- Re-reading notes multiple times

- Creating colorful study guides

- Reviewing flashcards by recognition

These methods feel productive. They create the satisfying sense of "doing something" with your study time. But cognitive science reveals a harsh truth: recognition is not recall.

When you re-read your notes, your brain recognizes the information and creates a false sense of mastery. "Oh yes, I remember this," you think, moving on to the next section. But recognition and true knowledge are fundamentally different cognitive processes.

Recognition happens when you see information and think, "I know this." It's passive, surface-level, and easily fooled.

Recall happens when you retrieve information from memory without prompts. It's active, challenging, and builds genuine understanding.

The problem with most study methods is they train recognition while exams test recall.

The Science of What Actually Works

Decades of cognitive research have identified two techniques that dramatically outperform traditional methods:

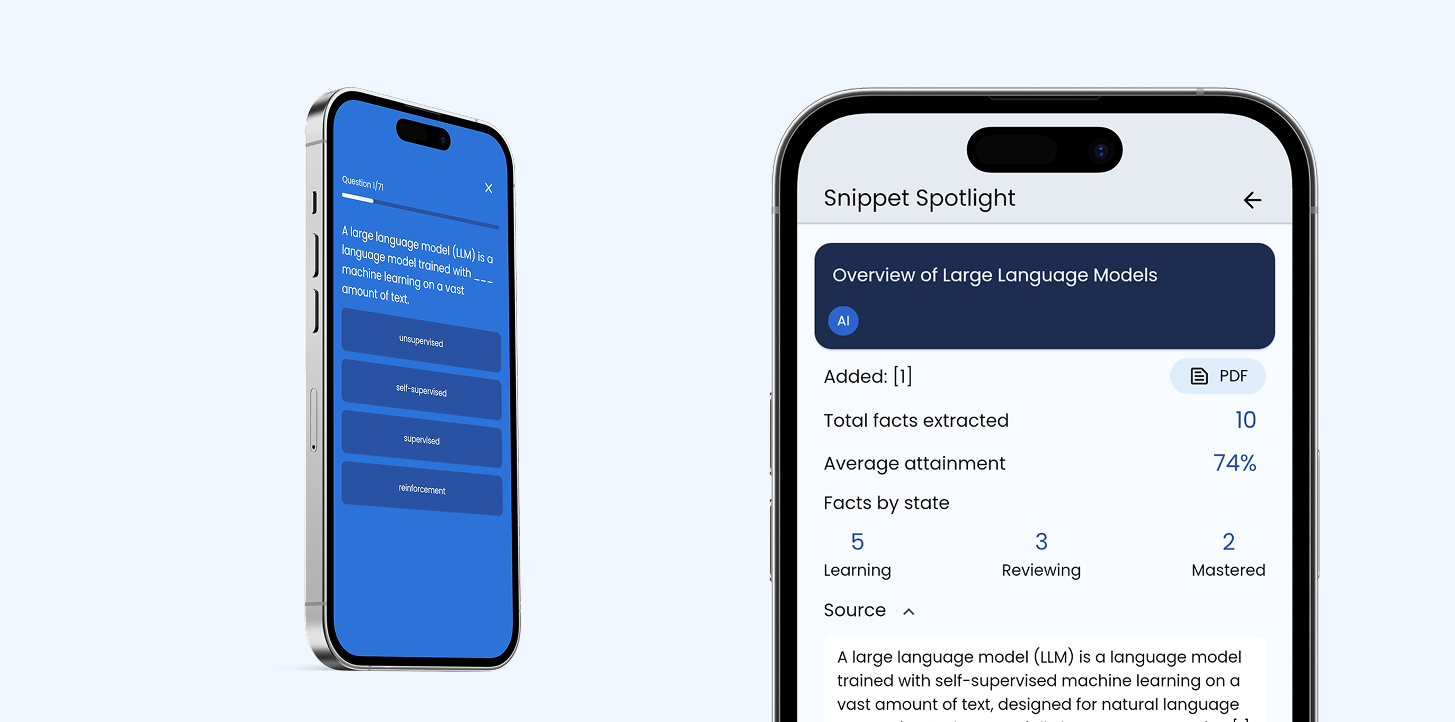

Active Recall: The Retrieval Revolution

Active recall forces you to pull information out of memory rather than simply recognizing it. In a landmark 2006 study, Karpicke and Roediger found that students who practiced active recall retained 80% of material after one week, compared to just 34% for those using passive methods.

The difference isn't small—it's transformational.

Active recall works because it mimics how you'll actually use knowledge. In exams, job interviews, or real-world applications, you don't have prompts or highlighted passages. You need to retrieve information from memory, often under pressure.

Every time you successfully recall information, you strengthen the neural pathways that store it. The struggle of retrieval—that moment when you're searching your memory—is actually the learning happening.

Spaced Repetition: The Forgetting Curve Solution

Even with active recall, timing matters enormously. Hermann Ebbinghaus discovered the "forgetting curve" over a century ago: without review, we forget approximately 50% of new information within one hour and up to 70% within 24 hours.

But here's the key insight: reviewing information just as you're about to forget it creates the strongest memory consolidation.

Spaced repetition spreads reviews across increasing intervals:

- First review: After 1 day

- Second review: After 3 days

- Third review: After 1 week

- Fourth review: After 2 weeks

- And so on...

This approach can increase long-term retention by 200-300% compared to massed practice (cramming). Instead of studying the same material daily, you study it less frequently but at optimal intervals.

Why Students Stick with Methods That Don't Work

If active recall and spaced repetition are so effective, why do most students still rely on highlighting and re-reading?

Familiarity and Comfort: Traditional methods feel safe because they're what everyone does. Breaking away requires courage and trust in unfamiliar techniques.

Immediate Gratification: Highlighting feels immediately productive. Active recall feels difficult and uncertain—which is exactly why it works.

Lack of Systems: Active recall and spaced repetition require organization and planning. Most students don't have systems to implement these techniques effectively.

Misunderstanding Difficulty: When active recall feels hard, students often think they're doing something wrong. In reality, that difficulty is the mechanism of learning.

The Implementation Challenge

Understanding these principles is one thing. Implementing them consistently is another.

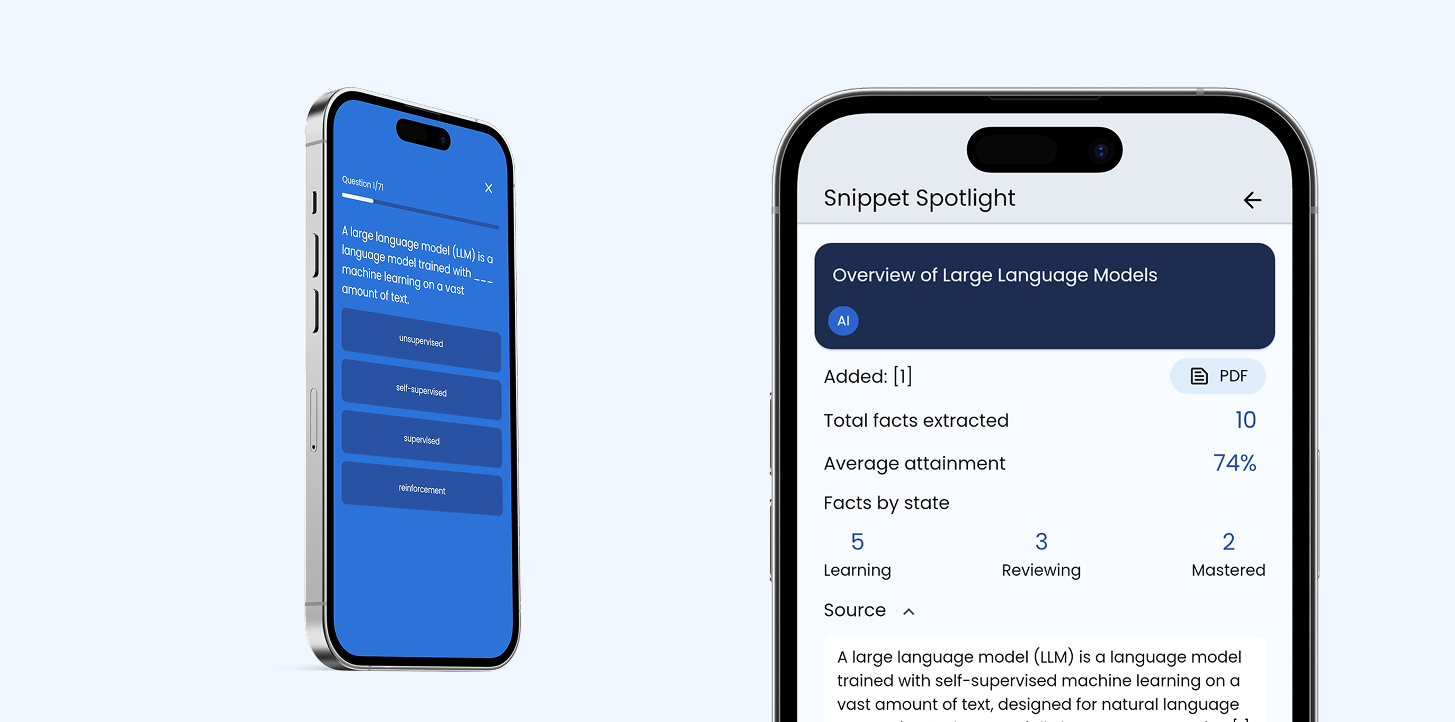

Traditional spaced repetition requires:

- Manual scheduling of review sessions

- Tracking what needs review and when

- Creating varied questions for each concept

- Adjusting intervals based on performance

- Maintaining motivation through the inevitable difficult periods

Most students give up because the administrative burden becomes overwhelming. They understand the theory but lack the tools to make it practical.

The Path Forward

The gap between knowing what works and actually doing it is where most students fail. But what if you could automate the proven science of learning? What if a system could handle the scheduling, question creation, and performance tracking while you focused on the actual learning?

The next evolution in studying isn't about working harder—it's about working smarter. It's about building systems that make the most effective learning techniques as easy as highlighting a textbook.

Your study habits shape not just your grades, but your entire approach to learning and growth. The question isn't whether you'll study—it's whether you'll study in a way that actually works.

Why Traditional Study Methods Are Failing Students (And What Actually Works)

How to Turn Any Content Into Long-Term Knowledge: The Brain Bricks Method